I hope things don't go back to normal, because if they do, it will mean that the deaths of thousands of people around the world were in vain. The changes are already on course. We can't go back to that rapid pace of life, turn the ignition on in all those cars, rev up all those machines at once. It would be tantamount to accepting that the earth is flat and that we ought to go on devouring it and one another. Then we will have proven that humanity is a lie.

— Ailton Krenak, April 2020

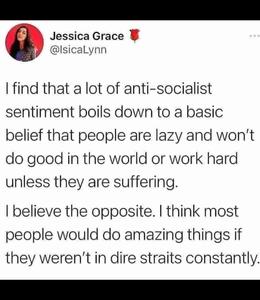

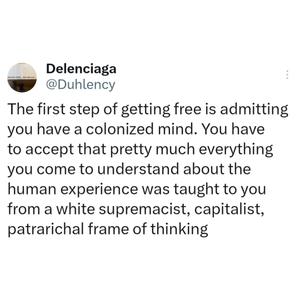

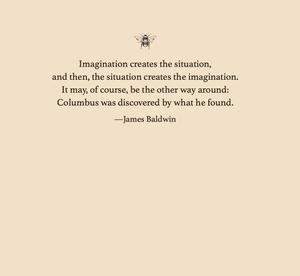

While communities existed prior to Enlightenment theory, it isn't clear that society, as such, did. With the development of the concept, the Enlightenment both created and analyzed the idea of society and the social human being. Yet it was not just any conception of sociality that interested the Enlightenment scholars; rather, it was sociality generated by commercial society, and a sociality that simultaneously centered cooperation and competition. The concept of society captured in the Enlightenment is in many ways a cynical, painful, and frustrating endeavor far removed from utopian thought at the time. In fact, Enlightenment theorists often argued that it was just this social friction that bonded society together: not the force of our love, affection, or tenderness for each other, but a cynical desire to best another, to extract wealth or resources, or to gain power and prestige.

— Nathan DuFord

Were we able to stand outside our own experience for a moment, we would probably realize that our perceptions of a great many things resemble more closely what we think about them than what they actually are. The earth has had countless other configurations, many of them without us on it, so why is it that we cling so stubbornly to this idea of the earth as humanity's backyard? The Anthropocene plays such a dominant role in shaping our existence, our collective experience, and our idea of what humanity means. Our adherence to a fixed idea that the globe has always been this way and humanity has always related to it the way it does now is the deepest mark the Anthropocene has left. This mental configuration is more than an ideology, it’s the construction of the collective imaginary — various generations in succession, layers upon layers of desires, projections, visions, whole cycles of life inherited from our ancestors, which we have honed and chiselled into a version we feel...

“Capitalism survives by forcing the majority, whom it exploits, to define their interests as narrowly as possible. This was once achieved by extensive deprivation. Today in the developed countries it is being achieved by imposing a false standard of what is and is not desirable.”

— John Berger, Ways of Seeing (1972)

Lest you get discouraged about changing the corrupted minds of fascists and genociders, remember that that is not the only angle.

We are also stopping their influence by not allowing them to control the narrative. We do this by withdrawing our energy, resources, attention, and time from their corporations and dominance, and eventually showing them we do not need them at all. Oppressors set up the world to make us think that we need them, but it is that they need us.

They need to have influence over us to hold their power.

But we are the influence, and we can take back our power completely.

Our time, attention, data and labor are their everything.

We are the reason for their entire existence.

We are their whole world.

We are the influence.

We are the outcome.

We determine the next move.

“There exists a multibillion-dollar Soft Power (Dream) Industry, which is in the business of crafting and selling powerful myths that lull us into various states of zombielike consumerism—swiping, subscribing, and submitting to its narrow vision of belonging. This Capitalist Dream skips along to the beat of the New York Stock Exchange’s trading-floor bells, inviting us to dance along to the notification pings of our latest Amazon Prime delivery. As historian Robin D. G. Kelley asks, “Even if we could gather together our dreams of a new world, how do we figure them out in a culture dominated by the marketplace?”

— Ruha Benjamin

The times we're living in are expert at creating absences: sapping the meaning of life from society and the meaning of experience from life. This absence of meaning generates stringent intolerance toward anyone still capable of taking pleasure from simply being alive, from dancing, from singing. There's still a whole constellation of little groups of people who dance, sing, make it rain. The kind of zombie humanity we're being asked to join can't bear so much pleasure, so much fruition in life. So they holler on about the end of the world in the hope of making us give up on our dreams.

— Ailton Krenak

about 2 months ago

Imagine we were to travel back 50,000 years in time. How did we interact in those hunting and gathering days? How did we conduct ourselves when there was no code of law, no courts or judges, no prisons or police? Hobbes thought he knew. ‘Read thyself,’ he wrote: dissect your own fears and emotions and you will ‘thereby read and know what are the thoughts and passions of all other men upon the like occasions.’ When Hobbes applied this method to himself, the diagnosis he made was bleak indeed. Back in the old days, he wrote, we were free. We could do whatever we pleased, and the consequences were horrific. Human life in that state of nature was, in his words, ‘solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short’. The reason, he theorised, was simple. Human beings are driven by fear. Fear of the other. Fear of death. We long for safety and have ‘a perpetual and restless desire of power after power, that ceaseth only in death’. The result? According to Hobbes, ‘a condition of war of all against...

There is a long philosophical tradition, dating back to Thomas Hobbes, which sees humankind as engaged in a war of “every man against every man.” Hayek believed that this frantic competition delivered social benefits, generating the wealth that would eventually enrich us all. But there is also political calculation. Together we are powerful, alone we are powerless. As individual consumers, we can do almost nothing to change social or environmental outcomes. But as citizens, combining effectively with others to form political movements, there is almost nothing we cannot do. Those who govern on behalf of the rich have an incentive to persuade us that we are alone in our struggle for survival and that any attempts to solve our problems collectively—through trade unions, protest movements, or even the mutual obligations of society—are illegitimate or even immoral. The strategy of political leaders such as Thatcher and Reagan was to atomize and rule.

— Monbiot and Hutchison, 2024

Sophie From Mars: "Our picture of the end of the world tends to depict people fighting over tiny scraps while bloody tyrants are the only ones able to create stable bubbles of social cohesion through violent enforcement, but that picture of some kind of world “after society collapses” actually comes from a particular ideological lineage. This all relates to the work of philosopher Thomas Hobbes, who Andreas Malm and other climate politics writers have spilled a lot of ink discussing and debunking. Hobbes, who lived during the English civil war, authored a book in 1651 called Leviathan, a seminal piece in social contract theory, and his argument was essentially that only a powerful, undivided body could rule in such a way that would create peace and stability. The first political influencer to have a strong thumbnail game, Hobbes gave Leviathan a frontispiece depicting the king as a giant made up of people, an enlightening depiction of the nature of...